"What Happens To The Alewife Happens To Us"

The last few weeks have been important for the future of the Skutik (St. Croix) River.

Not only did we see alewife (also called gaspereau) continue to migrate up the Skutik to their spawning grounds, but we saw many of the people who make decisions affecting the river come together to sign an historic Statement of Cooperation.

The document, between Peskotomuhkati leaders and many government agencies, commits to the restoration of the Skutik, a river whose health is key not only to the animals and people that live along its shore, but also to the groundfish, seals, whales, and seabirds that frequent Passamaquoddy Bay, the Bay of Fundy, and the Gulf of Maine.

I was honoured to be present for this signing. But before I go further into the significance of that moment, it’s important first to understand how the Skutik came to be in the state it is now, and how much more restoration work remains.

Troubled Waters

The Skutik River, its estuary, and Passamaquoddy Bay have always been at the heart of Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) territory and culture.

The Peskotomuhkati were, and are, faithful stewards of the river. But for the past 200 years, the Skutik has been degraded and mistreated by activity largely from settlers, such as dam construction and pollution discharges into the river.

A major blow came in 1825 when the Union Dam (no longer present) between Calais, ME, and Milltown, N.B., was built without a fish ladder and no way for migrating fish to get past the dam.

Salmon, alewife, shad and other fish that had always migrated up the Skutik to spawn were severely depleted, and the many animals that rely on the fish, as well as the Peskotomuhkati people, were impacted by the loss of vital and nutritious sources of food.

This decimation of fish runs continues today. Tremendous efforts have been undertaken over the years to maintain a (albeit greatly reduced) presence of some species like alewife, while other species, like Atlantic salmon, have been lost from the river altogether.

The Peskotomuhkati, and other allies like the Conservation Council, have long expressed concern for the plight of the river and the fish that should be allowed to migrate freely.

The most recent wave of concerted effort to restore the Skutik began in 2010. While the efforts seek to restore all native fish populations, initial focus is on alewife, a searun river herring that is a keystone species (meaning it is critical to the ecosystem—pretty much everything eats it, including me; I had some smoked alewife at the signing ceremony).

The most important factor in the renewed restoration effort has been the formation of the Schoodic Riverkeepers, a group of Peskotomuhkati people who came together to educate their community, people who live on their territory, and the governments who operate in Peskotomuhkati Territory.

The Riverkeepers have been formidable advocates for the Skutik, leading efforts to successfully repeal a Maine State law blocking fish passage at the Grand Falls Dam in 2013.

Since then, a range of actors—including the Skutik Riverkeepers, the three Peskotomuhkati Tribal communities, Maine, U.S., and Canadian governments, and NGOs like the Conservation Council, Eastern Charlotte Waterways, Atlantic Salmon Federation, and Downeast Salmon Federation—have all been working to improve the health of the river.

We do this by monitoring fish (counting and tagging fish to understand their movements and needs); assessing and removing or improving barriers to fish (teams have visited almost every culvert and dam in the watershed to see if fish can pass); educating local residents, landowners and officials about the health of the ecosystem and the need for restoration; and working with various government agencies to ensure that they are doing all in their power to help the river.

While a lot of work remains to be done, these efforts have seen much early success.

In 2002, when fish had to be trucked in tanks to their spawning grounds above impassable dams, the Skutik experienced a modern record low of 900 alewife migrating up its waters.

The decades of restoration work since have had a clear effect: Last year, we saw 550,000 alewife make the annual trek, and this year we’ve already counted more than 600,000 at the fishway in Milltown.

While this is an impressive improvement, research and historical accounts tell us that the Skutik can theoretically support 88 million alewife, meaning we have a long way to go to fully restore their population.

A major development on that front is NB Power’s decision to restore the historic Salmon Falls between St. Stephen/Milltown and Calais, ME, by removing the Milltown Dam. This means that the first major barrier to fish in the river is slated to be gone by the time fish return in spring of 2023.

The Peskotomuhkati Nation has also prepared a restoration plan to guide efforts on the Skutik, which is also being embraced by governments, NGOs and funding agencies.

So, finally, let’s get to what happened over the last few last weeks.

Return of the Alewife Run

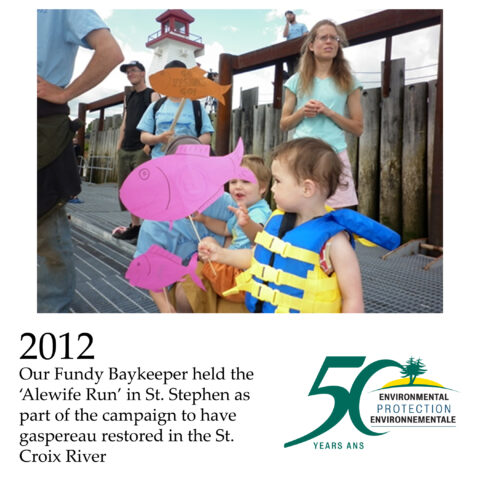

The Schoodic Riverkeepers hosted an 80-mile Alewife Relay Run, part of a Wabanaki tradition of sacred runs, to raise awareness around the importance of alewife migrating up the Skutik River to spawn as they have done for thousands of years (a similar run was held in 2012 as part of a campaign to see the river opened to alewife at the Grand Falls Dam. That year, the Conservation Council organized a water-based Alewife Run in conjunction with the land relay, to symbolically escort the alewife upriver).

Following the sacred run, on Thursday, May 26, a ceremony was held to sign the Statement of Cooperation between Passamaquoddy leadership and leaders from U.S. federal agencies, Maine state agencies, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada that pledges “to continue to work together toward the common goal of restoring alewives and other sea-run fish to this magnificent river, which will restore the cultural connection between the people of the Tribes/Nation and the Passamaquoddy Bay ecosystem.”

Unfortunately, New Brunswick’s government chose not to sign on to the statement.

While the statement of cooperation is not legally binding on signatories, it does, with the Peskotomuhkati’s restoration plan, provide a clear path forward for collaboration.

Many of the agencies who signed the statement have already demonstrated their commitment to the Skutik by funding the Peskotomuhkati Nation and NGOs to do work in the Skutik watershed, or by doing work directly such as conducting studies into fishway improvements or replacements.

The Skutik has been mistreated for a long time, and it takes a great deal of effort to even begin to put things to rights.

That work is underway, and it is important that we celebrate our early successes and resolve ourselves to continue to do what’s right for the river.

The Alewife Run and the signing of the statement of cooperation are powerful testaments to the resolve of those who love this river. For, as Schoodic Riverkeeper Vera Francis says, “What happens to the alewife happens to us.”

Share this article with your friends and family and invite them to add their voice!