Last week, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released the draft results of its study on the relationship between hydraulic fracturing and drinking water. There has been lots of interpretation, but what does the study really say?

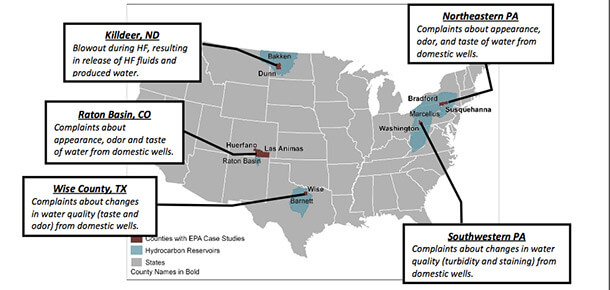

The report clearly states that fracking activities have resulted in “impacts on drinking water resources, including contamination of drinking water wells,” but the EPA researchers “did not find evidence that these mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources in the United States.”

The phrase ‘did not find evidence’ is key here. It doesn’t mean pollution isn’t happening, just that the EPA couldn’t find evidence in the data it was able to obtain and study for this report. When data is not being adequately collected, it is no surprise that evidence is not found.

The EPA even points this out, saying the lack of widespread impacts could be due to “other limiting factors” — such as gaps in the data it was able to study.

In fact, as the Pulitzer Prize-winning news agency Inside Climate News reported in March 2015, “the EPA couldn’t legally force cooperation by oil and gas companies, almost all of which refused when the agency tried to persuade them [to provide information].”

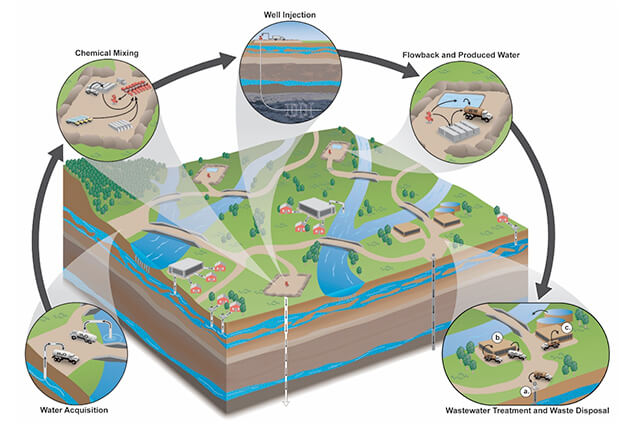

Over the course of the study, the EPA encountered data gaps in every topic it researched, including:

- baseline water quality data,

- the frequency of fracking fluid and wastewater spills,

- the composition of wastewater and fracking chemicals, and

- the number and location of hydraulically-fractured wells

The EPA addressed these shortfalls in its report, saying the “data limitations” it encountered meant it was impossible to know with certainty just how often fracking activities polluted drinking water in the U.S. In the days following the release of the report, fracking proponents have used the EPA’s lack of evidence as proof the activity is safe, when in fact, the EPA only determined that we still don’t have enough reliable information to know with confidence how fracking will impact drinking water.

Speaking to media in New Brunswick shortly after the report was released, Tom Burke, lead science adviser to the EPA, said it would be a false interpretation to claim the EPA study gave a green light to fracking. “No, it was never a study designed to determine whether fracking is safe or not,” Burke said in the June 11 interview. “It was a study determined to look at the use of water and the potential vulnerabilities of our drinking water resources.”

The cautionary tale of the EPA’s conclusion joins the ranks of other fracking reviews released this past year, from the Council of Canadian Academies, the New York State health commission and NY State Department of Environmental Conservation.

The Council of Canadian Academies’ report, commissioned by the Canadian federal government, included 14 experts and determined, among other things:

- There has been no comprehensive investment in the research and monitoring of environmental impacts

- Water contamination from leakage around improperly sealed well bores and migration through geological fractures, poses the largest risk from the industry

- In places where development and people intersect (like New Brunswick), special considerations must be made for the appropriateness of the industry, especially if those populations are dependent on groundwater wells.

- There is a lack of knowledge of health and social effects from development

Both the New York State Department of Health and Department of Environmental Conservation issued reviews — in December and May, respectively — which led New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo to announce his plans to ban the practice, saying:

- Drinking water can be impacted from underground migration of methane and/or fracking chemicals associated with well construction

- There would be intolerable human health and environmental costs, including degraded air quality from increased amounts of vehicle exhaust and particulate matter in the air, and possible groundwater and surface water contamination from poor well construction and chemical spills

These three studies also considered the climate change impacts of further shale gas extraction and all concluded that:

- Methane releases increase greenhouse gas emissions and pose a problem for shale gas extraction,

- If shale investment moves capital away from renewable power, it could make the climate change situation worse, and

- Policies directed towards achieving substantial reductions in GHG emissions means reducing reliance on all fossil fuels, including natural gas.

Just this past week, the G7 countries — including Canada — signed a declaration to cut greenhouse gases by phasing out the use of fossil fuels by the end of the century.

The commission tasked with reviewing the conditions of the fracking moratorium here in New Brunswick has one year to report its findings to government.

The Conservation Council of New Brunswick hopes the commission will meet and listen to organized local community groups across the province, especially those in impacted areas; examine the potential for job creation from investments in energy efficiency programs and renewable energy; and communicate with expert scientists, particularly those involved with the Council of Canadian Academies, the New York State Health Commission, and our own Chief Medical Officer of Health.