Dr. Matthew Betts says smart silviculture and smart forest planning would meet the needs of forestry companies and support a diversity of life in our forests

New Brunswick’s approach to managing its forests, built around large-scale clearcuts and herbicide spraying, is driving a significant decline in the diversity of life found in our woods—but it doesn’t have to be this way.

This was the message Dr. Matthew Betts gave to MLAs on the Standing Committee on Climate Change and Environmental Stewardship on Wednesday, June 23.

Betts, an honorary research associate at UNB Fredericton and forestry professor at Oregon University, presented to the committee as part of its weeklong meetings examining glyphosate use in our forests.

Betts has been back in his native New Brunswick for 10 months conducting a study to determine how the province’s forestry management regime affects bird populations.

To his knowledge, it’s the first study of its kind in New Brunswick.

“Birds are seen broadly as biodiversity indicators—it goes all the way back to people having canaries in coal mines back at the turn of the century in New Brunswick,” Betts told committee members.

“Our understanding of DDT first emerged at least partly because people started noticing eggshell thinning in birds, and that led to the cessation of DDT in many parts of the world. Birds also have been some of the harbingers of climate change. They were the first species really to be shown to extend their range northwards as the climate warmed in the U.K.”

What are birds telling us about forest management practices in New Brunswick? A bleak story.

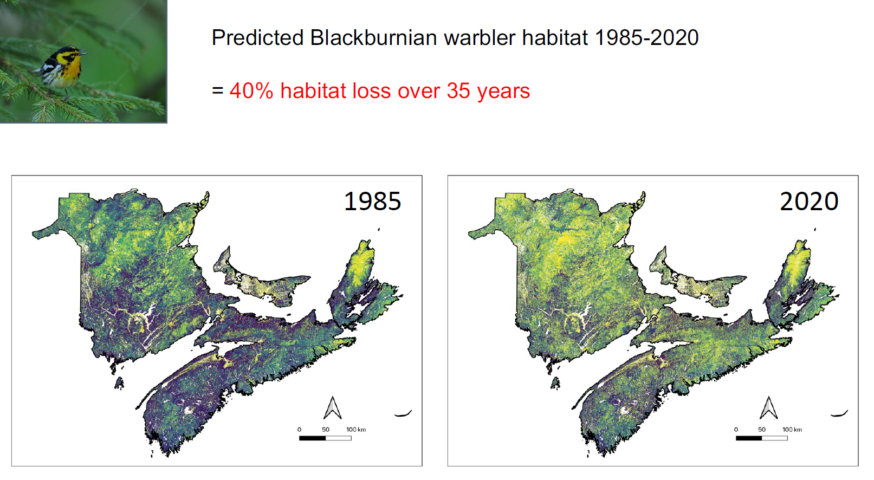

Betts’ research, which is currently under peer review, found that 90 per cent of New Brunswick’s most common birds have experienced habitat loss in the last 10 years, and this habitat loss has led to substantial population declines.

His modelling estimates there are between 33-104 million fewer birds in our forest today than in 1985.

Why is this happening? In a nutshell: “Intensive forest management is increasing plantation and clearcut areas, and that’s not regenerating at the same rate as its being harvested and this is driving habitat loss for the 54 most common bird species, and habitat loss is associated with population declines.

“If this is happening to birds, we just don’t know what is happening to more specialized species, like the flying squirrel or American marten.”

Betts says this evidence poses the question: what should be the future of New Brunswick forests?

“Do we need to trade biodiversity for wood and jobs? I’m optimistic. I don’t think that we do. I think we can continue to produce wood, it just takes intelligent silviculture and intelligent planning. And we can slow or stop these bird declines and the habitat loss.”

Intelligent silviculture involves growing and harvesting trees without using herbicides and without clearcutting—or, at least, without the large-scale clearcuts New Brunswick currently allows.

Betts said forest management should shift to a focus on the quality of wood harvested over quantity and rely on natural regeneration, noting selective or partial cutting practices lend themselves well to New Brunswick’s shade-tolerant tree species.

“[Red spruce] can manage shade for a long time, and when the canopy opens up, they’re released and they grow. So if I went in there with a saw and cut down a patch opening or a few-tree opening, you’d get natural regeneration— no need for herbicides at all. That’s a really important message.”

Betts said the first thing the Department of Natural Resources and Energy Development should do is immediately end clearcutting in New Brunswick’s remaining stands of mature old growth forest.

“We should stop clearcutting in those areas, honestly. They don’t need to be in reserve—some of them should be—but for the remaining ones, we should be doing smart silviculture. And I can say as a former forestry student, it’s way more fun doing that kind of silviculture. There is so much more creativity involved with going out into a stand and figuring out which trees to cut and which ones to leave, and how you are going to regenerate without herbicides.”

“Herbicides … obviously are of toxicological concern,” Betts said. “But I’m trying to point to the broader issue, which really has to do with the forest management regime we use, of which herbicides are a part. And I wanted to point out that there are alternative ways. I think that the regime is resulting in these wildlife population declines, not as a direct toxic effect of herbicide—or highly unlikely—more just because of habitat loss.

“We’re changing our forest. If you’ve driven around New Brunswick you’re probably quite aware that it looks different now than it did 30 years ago. And the question is, how much of that change is too much?

Have your say

Recommended links:

- Watch Dr. Betts’ full presentation to the Standing Committee

- Have your say: Use our letter-writing tool to call on your MLA and standing committee members to end herbicide spraying in our woods

- Glyphosate update: Lois Corbett presenting on spraying and outdated forestry practices at Standing Committee

- Then and Now: What the Auditor General says about forest management in NB