A guest commentary by Ron Smith

A recent decision by the New Brunswick government to enter into guaranteed wood supply contracts with forest companies, also referred to as the New Forest Strategy, has generated arguably unprecedented debate in the public arena. Much of this debate has focused on a lack of transparency or consultation. Until such time as the full agreement can be reviewed, much speculation will continue. I am, without apology, contributing to this speculation.

The basic premise of the following article may be a little different from some of what has previously been put in the public forum. I want to start with stating that I totally agree that there has not been meaningful consultation prior to the announcement of the signing of this new forest strategy. It appears that much of the previous ‘public consultations’ have been largely ignored. As has been openly admitted, until such time as the actual agreement is released, it may be unfair to criticize the details. However, I would like to argue that this is but yet another example whereby the approach to managing New Brunswick Crown lands (PUBLIC lands) is too narrow. The net result of having in the past, and continuing to adopt a narrow approach to forest management, means we have not, and are not, receiving anywhere near the economic, social and environmental benefits that we could and should have.

The loss of economic opportunities may not be as readily apparent. I would argue that there are economic opportunities that have been largely ignored even in the previous studies when there was meaningful public consultations. The debate has focused on how much wood to harvest, how often, and the economics of harvesting. Management decisions have been made based on what impact of any given decision will have on wood supply. This type of forest management model is too simple. Instead, we should try to consider co-managing for more values. What about ‘everything else’? This everything else I will refer to here as non-timber forest products (NTFPs).

Key Issues and Assumptions

What are some of the key issues? (Note: the following key points have been extracted from a number of sources and opinion pieces that have been released in the media, including open letters etc.). The purpose of reiterating some of these concerns is to set the base for discussing what economic and social opportunities may likely be lost if this new strategy is implemented. Here are four key issues.

1. The ‘true’ cost to the public is being ignored: This contract, if ratified will ‘guarantee’ wood supply to the companies, particularly JD Irving Ltd. The shift is towards what is being spun as ‘outcome-based’ forest management. In reality it is little more than a guaranteed wood supply at a cost that is acceptable to the company; NOT at a cost that is good for the taxpayers of New Brunswick. On the contrary, it appears that it is clearly going to cost the public to honour this contract.

2. First Nations have been virtually ignored: While there has been some token references to First Nations, this contract is all about increasing wood supply to industry and as a result, further diminishes access to the types of forest and the multiplicity of resources (both consumptive and non-consumptive) that First Nations have traditionally valued. It will clearly impact on Aboriginal and treaty rights but there has not been any consultation!

3. Conservation values are being ignored: The rules that currently protect wildlife habitat, rivers and patches of old forest are being rewritten. For example, it has been reported that the New Brunswick’s Department of Natural Resources staff have cautioned against reducing conservation forest below 28%, anything less would not be sustainable according to their own wildlife biologists and forest ecologists. Conservation forest includes wildlife habitat, river and stream buffers, deer yards and old forest. New Brunswick’s forest plan slashes conservation forest on public lands from 30% (or 28%) down to 23%.

4. The number of jobs we are being told that will be created is questionable: On the surface, the contract has been signed using the laudable goal of increased employment as a rationale. But does it actually do this and are the taxpayers of NB getting a good or bad deal? Five hundred new forestry jobs are supposedly going to be created. The 500 jobs estimate includes direct and indirect jobs. However, internal government documents suggest that only 200 direct jobs will actually be created, while an estimated 300 indirect jobs are expected to arise from the ether. To answer the question of is this good value or not the economy, a quick comparison of the numbers of jobs created per unit of ‘new wood’ harvested is in order.

If we want to use public wood to create jobs, the less wood required per job the better. Using Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) statistics for employment and wood volume harvest at the national and provincial levels, 2012 data shows that New Brunswick directly employed one person for every 775 cubic metres of wood harvested. At the national level, Canada creates one job from just 630 cubic metres of wood. Ontario only needs 246 cubic metres of wood to create each direct job. So right away the question arises: Why are we using 3,300 cubic metres of new Crown wood to create each new job when as an industry New Brunswick currently employs one person for each 775 cubic metre of wood? Even if we assume 500 direct jobs will be created, that still equates to an expensive 1,320 cubic metres for each new job.

What are the potential impacts on NTFPs and what opportunities are being missed for truly generating long-term economic benefits to New Brunswickers?

Loss of NTFP species due to the shift from old growth forests to juvenile plantations and (or) conifer forests.

For a decade now, we have seen a doubling in the area of allowable clearcuts from 100 ha to 200 ha. The sequential clearcutting of patches is in effect changing the forest landscape at a scale never before seen in New Brunswick. The shift is to a much younger forest landscape. The new forest plan will eliminate a standard that is used to preserve the native Acadian forest type. Essentially, forestry companies will be allowed to clearcut in areas previously designated as select cut only zones; this will increase the area of clearcutting in New Brunswick’s forest by 10 per cent. Forest management practices associated with clearcutting by their very nature will eliminate many NTFP opportunities.

Chanterelle mushrooms grow in shade under a variety of older growth stands, both conifers and hardwoods. However, regardless of the species, they require deep, old leaf litter. This critical habitat factor is lost following clearcutting and plantation establishment for a considerable time, likely 30+ years. Where it has been studied such as in the Pacific northwest, chanterelles were clearly more predominant in older (40-60 year old stands) than younger ones. Currently in NB, chaga is harvested. But it only grows on older white and yellow birch. Most of these are also being eliminated. There are other plant species associated with mature Acadian forest habitat that will also be negatively affected including species valued in both traditional Aboriginal and western medicines, edible plant and mushroom species, and other uses such as oils and resins. For example, we have a company in New Brunswick that currently produces value-added anti-cancer drugs using needles and small twigs of Canada yew, also known as ground hemlock. This species also naturally grows under the shade within mature Acadian forest canopy, most often associated with yellow birch. Already, much of the biomass supply for this industry is being imported from other provinces.

Herbicide spraying changes the forest flora removing a number of NTFP opportunities including berries (raspberries, blackberries, and blueberries to mention a few). Herbicide (i.e. glyphosate) is also effective in eradicating species such as sweet fern, sweet gale, Labrador tea, wintergreen, and a variety of other herbaceous species that could be harvested for essential oils. Fruit and nut producing species such as beaked hazel, highbush cranberry, choke cherry, and sumac are also reduced in abundance. All of the above species represent small-scale economic opportunities that are being lost. Furthermore, we already have small-scale businesses that use ALL of the aforementioned. Small-scale, value-added businesses are easily ignored in the process of creating softwood plantations because the dollar value associated with any one, is touted as being insignificant. However, it has been clearly shown in other jurisdictions that when community-based cooperative ventures are supported, meaningful economic benefits are the net result. Access to the resources on “public” lands are typically a critical component to these success stories.

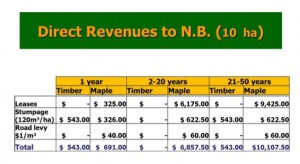

The maple sugar industry in New Brunswick has been lobbying, with little success, to increase the amount of Crown land made available for sugar bush leases from 0.5 to 1%. If you look at the jobs created AND the amount of revenue given to the province from annual leases, the best end-use for tolerant maple stands is clearly as sugar bush, NOT biomass or timber. The following table, using 2012 NBDNR posted figures, illustrates the economic return to the province of managing a 10 ha block of sugar maple for timber versus sugar bush. The revenue under the timber column represents actual stumpage paid. The number of jobs created per ha are similarly significantly higher in sugar bush operations.

Table 1. Summary of direct revenues to the province of New Brunswick generated from managing a 10 ha block during three time periods.

Ecotourism, and other non-consumptive uses of the forest appear to also have been ignored. The loss (real or perceived depending on which side or the argument you take) associated with further reducing mature Acadian forest also has a negative impact on the opportunities for viewing wildlife species that require mature habitat. Unlike large-scale commercial wood harvesting, managing for many NTFP values IS compatible with other economic ventures. This synergism is also being ignored or dismissed as not important. New Brunswick entrepreneurs are losing these opportunities when access to the forest resources are taken away through signing long-term fibre agreements without consultation.

Opportunities for Aboriginal traditional uses of the forest (including non-economic harvesting) are also being diminished. Aboriginal and treaty rights represent a very contentious issue that continues. This new strategy has certainly not helped.

Small-scale does not mean that activities cannot be economically viable. Over the past few years, efforts to create community forest management cooperatives have met with rigorous opposition from the government. Instead of a willingness to support the creation of community forest management units which would require access to some Crown (PUBLIC) lands which were no longer being used by companies whose mills have closed, these lands were reallocated to other companie(s) for more of the same. There is a strong entrepreneurial spirit in New Brunswick but it is not being supported.

Managing some of our public forests (i.e., Crown Lands) to include Non-Timber Forest Products can significantly increase both the short-term and long-term ‘net’ economic benefits provided to rural communities and to the province. Our forests should represent more than a repository for wood and we need to truly diversify how we manage them if we are to start realizing their true potential. We need to start before it is too late!

Ron Smith, PhD, RPF, is an Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Forestry and Environmental Management, University of New Brunswick and a Private consultant for VarFor Ltd.