A four-year assessment of Canada’s freshwater resources, completed by World Wildlife Fund-Canada (WWF-Canada), has found all of Canada’s freshwater watersheds are ‘under tremendous stress,’ including the Saint John-St.Croix and Maritime Coastal watersheds in New Brunswick.

WWF-Canada’s Watershed Report, the first national study of Canada’s freshwater ecosystems, assesses both the health and stresses facing all 25 of the country’s watersheds, which are made up of 167 sub-watersheds.

The study found that every watershed is facing many environmental threats related to human activities such as pollution, agricultural runoff, habitat loss, oil and gas development and hydroelectric dams. The report’s authors say Canada’s watersheds are under a tremendous amount of stress. Almost two-thirds of sub-watersheds have poor to fair water quality rankings and are already enduring the impacts of climate change. Just as concerning, in 110 of the 167 sub-watersheds, there wasn’t enough data to paint a complete picture of watershed health.

How did New Brunswick measure up?

Let’s take a look at the results for New Brunswick’s two major watersheds, the Saint John-St.Croix and the Maritime Coastal watershed, to see how we compare to the rest of Canada.

Threats

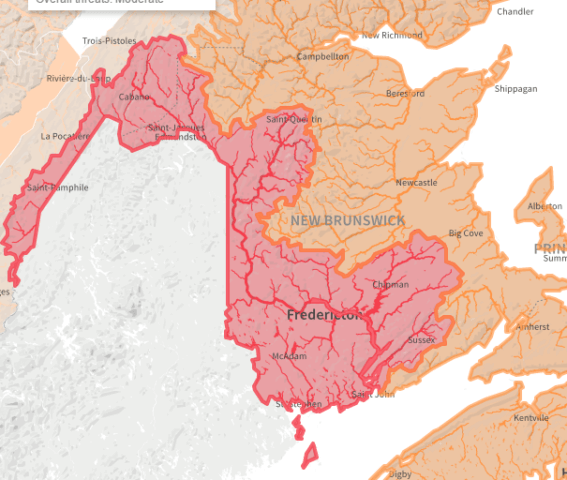

The overall threat in the Saint John–St. Croix watershed is high. Pollution levels are rated very high, attributed to contaminants in agricultural runoff, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, and pollution from municipal and industrial sites, such as pulp and paper processing and water treatment facilities.

Dams, roads and rail infrastructure create a high level of fragmentation throughout the watershed. Alteration of flow and habitat loss are both currently moderate, with several reservoirs affecting flow, and forest loss reducing available habitat. The current impact of climate change is rated as low, but, as the report states, this score does not reflect the potential for future change and the risk of coastal flooding, which may pose significant threats in the future. Lastly, the levels of water overuse and invasive species in the Saint John-St. Croix watershed are both rated low.

The overall threat level in the Maritime Coastal watershed is rated moderate. The threat level rises to high, however, in three of the five sub-watersheds: the Prince Edward Island sub-watershed, Bay of Fundy and Gulf of St. Lawrence sub-watershed and Southeastern Atlantic Ocean sub-watershed. Pollution ranks as the No. 1 threat, with the threat level for the whole watershed being very high, again due to agricultural contamination and pollution from municipal and industrial sites. Roads and railway crossings create high levels of habitat fragmentation in each sub-watershed. Threats associated with invasive species, overuse of water and alteration of water flow remain low across the watershed.

Health

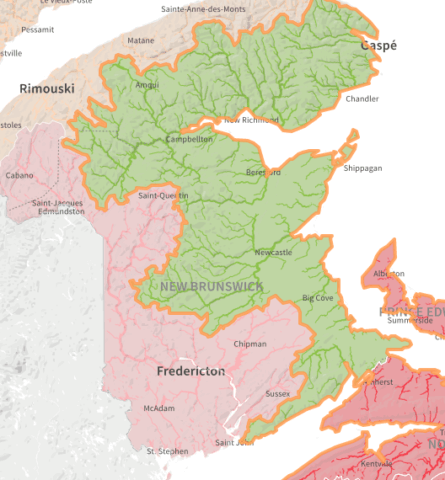

Overall, the health of the Saint John–St. Croix watershed is rated good, with a very good rating for flow. Benthic invertebrates — the “bugs” that live on the river bottom, such as flies, beetles, aquatic worms, snails and leeches – score good. Fish health is also good. Based on available data, results show there has not been a decline in the number of native fish species in the watershed over time. Where the Saint John–St. Croix watershed doesn’t perform as well is on water quality, earning a fair rating because the level of certain contaminants exceeded the water quality thresholds at a number of sites between 2011 and 2015. For example, some metal concentrations regularly exceeded water quality guidelines during this period.

Due to a lack of data for fish and water quality, a health score could not be assigned for the Maritime Coastal watershed as a whole. However, the watershed was rated as very good for water flow and good for bugs. Only two of the five sub-watersheds have enough data to provide an overall health score. The Southeastern Atlantic Ocean sub-watershed scores very good while the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Northern Bay of Fundy sub-watershed scores good. Where fish data is available, there are good levels of native species. The Gulf of St. Lawrence and Northern Bay of Fundy is the only sub-watershed with sufficient data to produce a water quality score, which has been assessed as poor.

Where do we go from here?

While the results of this study paint a great picture of what is happening in our watersheds, it is incomplete.

A news release from WWF-Canada says that “even more alarming is the fact that as a nation, we don’t collect enough data to know just how much damage all this stress is causing.”

An important takeaway from this study is the glaring absence of data, not only in New Brunswick, but across Canada.

Traditionally, water has been regarded as a provincial or local matter, and in the past, monitoring has suffered funding cuts across all levels of government. As a result, not enough data is being collected which leaves us in the dark when it comes to understanding the state of our precious freshwater ecosystems. After all, how can we expect policy-makers to make evidence-based decisions on freshwater when the data needed is non-existent?

Canada’s watersheds are interconnected and WWF-Canada says that they are all facing similar threats, regardless of geographical boundaries. The report highlights the need for coordination and oversight at a national level, and ultimately recommends a national monitoring system that includes:

- multiple approaches to water monitoring, including citizen science

- collection of data for all aspects of freshwater health, taking into accounts local conditions, with real-time, monthly and annual reporting, and including as many indicators and contaminants as possible

- standardized reporting of data through the creation of nationally-linked regional hubs.

At a reception with WWF members in June, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau echoed the report’s findings.

“There’s so much we need to know and so little time in which to gather it, understand it and act to protect what we have for future generations.”

While there was no promise of a national monitoring system, Environment and Climate Change Canada has committed $197 million to improve ocean and freshwater science and monitoring.

Recommended Links

- An interactive map detailing the Watershed Report

- Read more on what we need to do to protect our treasured coastlines, here.

- Find out what we’re doing to protect freshwater in New Brunswick, here.